West Africa’s flagship integration project is commemorating its golden jubilee amid the paradox of what many fear is an institutional crisis.

Exactly 50 years ago – on May 28, 1975 – the historic Lagos Treaty gave birth to what was to be a regional bloc embodying the hope of a united, prosperous and integrated West Africa.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has since faced the usual trials and tribulations of any such bloc that undertakes the ambitious task of finding a common thread to bind often disparate interests.

However, what happened in January 2024 was a moment of reckoning like no other in ECOWAS’s history.

The departure of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger from the bloc represented more than a diplomatic setback; it signalled a fundamental shift stemming from decades of unfulfilled promises and a growing disconnect between ECOWAS institutions and the people they seek to serve.

The original endeavour, led by 15 countries, was intended to transcend the artificial boundaries drawn by colonial powers and forge a new, common path for economic prosperity.

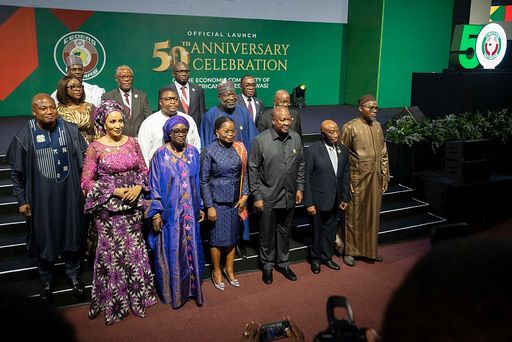

Five decades later, as the region's leaders gather in the Nigerian capital of Abuja to celebrate the anniversary, it is time to take stock.

For Nigerian President Bola Tinubu, who is the current chairman of ECOWAS, the bloc has contributed to the development of the region despite the challenges.

‘’Today, we celebrate not only five decades of history but the enduring spirit of unity, resilience, and shared destiny that defines our Community. In 1975, our founding leaders envisioned a West Africa where borders unite rather than divide — a region of free movement, thriving trade, and peaceful coexistence. That vision is still alive,’’ Tinubu said at the anniversary event in Lagos on Wednesday.

"ECOWAS is a beacon of African unity. In overcoming colonial legacies, we brought together Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone nations under one vision —an achievement of global significance,’’ he said.

"Our region has pioneered free movement, expanded intra-regional trade, and deepened integration through instruments like the ECOWAS Trade Liberalization Scheme and Joint Border Posts. These measures have facilitated business, cultural exchange, and mobility across West Africa,’’ President Tinubu added.

However, analysts say between significant successes, persistent structural challenges and recent crises that threaten the organisation's very foundation, ECOWAS finds itself at a critical turning point.

Genesis of a vision

ECOWAS was founded in a context marked by two major dynamics that defined post-independence West Africa: the urgent desire to overcome colonial divisions that had artificially separated peoples with shared histories and cultures, and the pressing need for economic integration in the face of the fragility of young West African states struggling to establish themselves on the global stage.

Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Togo signed the Lagos Treaty to create a common market, promoting free movement of people and goods, and strengthening political cooperation across linguistic and cultural divides that different colonial administrations had reinforced.

"In 1975, we decided to create this organisation based on a promise: that of equitable regional integration, where the largest would support the smallest, and where the smallest would also contribute," Beninese foreign minister, Olushegun Adjadi Bakari, tells TRT Afrika.

Yet, tensions and contradictions existed from the outset, foreshadowing challenges that would persist for decades.

Mauritania, the only Arabic-speaking state in the predominantly French and English-speaking bloc, left the organisation in 2000, citing cultural and linguistic incompatibilities.

When Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger formalised their withdrawals in a coordinated move last year, it not only further weakened regional unity but also called into question the sustainability of the integration project.

Bridges across borders

So, will history look at ECOWAS’s first five decades as just a litany of what could have been?

Despite the mounting challenges and periodic setbacks, ECOWAS can legitimately boast several significant achievements that have transformed the daily lives of millions of West Africans and established essential precedents for continental integration.

The 1979 Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, which gradually came into force over subsequent decades, has dramatically increased mobility across the region, reinforced by the introduction of the ECOWAS biometric identity card.

The technological innovation, a first in Africa, has facilitated seamless travel for millions of citizens.

Significant progress has also been made in systematically removing customs barriers and reducing trade restrictions, represented by major infrastructure projects such as the Abidjan-Lagos Corridor (1,028 km).

This economic corridor, involving an investment of US $42 million, aims to physically connect markets and facilitate more efficient trade flows between major regional economic centres.

Integration challenges

Although the free movement of people appears to be a success on paper and represents one of ECOWAS's most visible achievements, political tensions, entrenched cultural barriers, and widening inequalities persist, undermining the bloc’s integrationist aspirations.

President John Dramani Mahama of Ghana emphasised this point during the launch of the bloc’s golden jubilee commemoration in Accra on April 22. "Our citizens must feel that ECOWAS is not a distant bureaucracy, but a living community that responds to their needs and aspirations."

But significant obstacles persist that prevent this vision from becoming a reality.

Despite the theoretical freedom of movement enshrined in protocols and treaties, abusive controls at border crossings and systemic corruption still hamper mobility, creating frustration among citizens who expected integration to simplify their lives.

Economic disparities also pose a significant and growing challenge to regional cohesion. Nigeria, for instance, stands out in the regional landscape with its vast resources and a dominant domestic economy, driven by a population of 228 million.

With smaller neighbouring economies struggling to keep pace, the prospect of the chasm widening makes regional integration even tougher than it was over the past 50 years.

The lack of shared infrastructure also poses a fundamental challenge to deeper integration. Transnational projects – railways, highways and energy networks – are progressing slowly due to financing constraints, political disagreements and technical complexities, all of which limit the potential for economic convergence and closer ties between member states.

Integration's final frontier

One of the most significant and persistent criticisms of ECOWAS remains the absence of a single currency that would truly integrate regional markets and reduce transaction costs.

The Eco, originally scheduled to be rolled out in 2020 and then postponed to 2027, continues to be hindered by fundamental economic divergences between member countries, including differing fiscal policies, varying inflation rates, and disparate levels of economic development.

The benefits of a monetary union could be transformative.

For one, it would combat prohibitive foreign exchange costs, as transactions are currently often carried out in dollars or euros, draining scarce foreign currency reserves and imposing additional costs on regional trade.

Another potential benefit is the significant strengthening of intra-regional trade through reduced transaction costs and exchange rate uncertainties, which currently discourage cross-border commerce.

A third goal worth fighting for is enhanced monetary stability in the face of volatile fluctuations in national currencies, which undermine economic planning and investment decisions.

ECOWAS's Achilles heel

Experts view Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger's departure from ECOWAS as a potentially irreversible setback.

These three countries, all governed by military regimes, justified their withdrawal by denouncing ECOWAS as being "under foreign influence" and "far removed from the aspirations of its people”.

The allegations, reflecting deeper dissatisfaction with the organisation's approach to governance and regional affairs, portend a significant threat to the stability of a region battling persistent terrorism, recurring coups d'état, and questionable governance structures.

Experts warn that the troika’s departure from established ECOWAS cooperation mechanisms could weaken the "collective" response to terrorism and security crises, creating security gaps that extremist groups could exploit.

This development also risks fostering increased interference from foreign powers seeking to exploit the very divisions within the region that ECOWAS seeks to bridge.

ECOWAS’s loss translates into nearly 70 million inhabitants and a strategic portion of its territory, rich in natural resources that are crucial for regional economic development.

The newly formed Alliance des États du Sahel (AES) could now compete directly with ECOWAS's influence and institutional authority, weakening decades of carefully constructed economic and security cooperation frameworks.

Also at stake is the future viability of West African integration, especially the question of whether the ECOWAS model can adapt to changing political realities and evolving citizen expectations across the region.

Reimagining integration

At 50 years old, ECOWAS stands at the crossroads, facing the daunting prospect of determining its relevance for the next generation of West Africans.

Experts across the spectrum believe introspection holds the key.

The regional bloc’s next chapter will depend on its ability to address the fundamental challenges that have limited its effectiveness: reducing economic disparities, strengthening democratic governance, improving security cooperation and, most importantly, ensuring that the benefits of integration reach ordinary citizens.

Only by confronting these challenges head-on can ECOWAS hope to fulfil the ambitious vision that inspired its founders five decades ago in Lagos.

As Beninese foreign minister Bakari candidly puts it, "We must look at where we have stumbled."