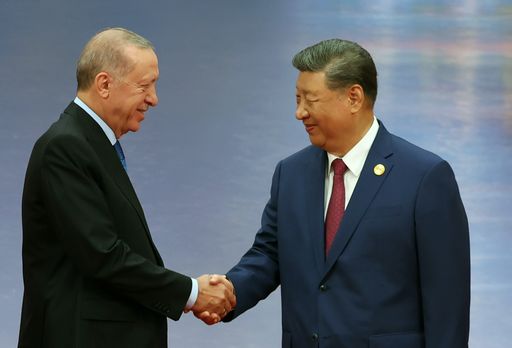

When President Recep Tayyip Erdogan addressed a host of global leaders at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in China’s Tianjin, it marked a pivotal moment for Türkiye as well as the bloc that represents 41 percent of the world’s population.

For Türkiye, the symbolism of Erdogan’s participation runs deeper than ceremony. Ankara is the first and only NATO member to hold SCO dialogue partner status, a distinction it has had since 2012.

This rare position highlights Türkiye’s deliberate effort to straddle two worlds: anchored in its traditional Western alliances, yet increasingly invested in Eurasian partnerships.

As global power fractures into rival camps, Ankara presents itself as a bridge between them—a country uniquely placed to navigate Brussels, Beijing, Washington and Moscow.

Under Erdogan’s leadership, Türkiye has steadily expanded its SCO footprint. In 2017, it chaired the SCO Energy Club, a role that placed Ankara at the nexus of Eurasia’s most critical resource discussions.

More recently, trade with China and Russia—the SCO’s two leading powers—has surged, underscoring the economic logic behind deeper engagement.

Yet Ankara’s interest in the SCO is not merely transactional.

For Türkiye, the organisation is also a gateway to Central Asia, where Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan—founding SCO members—share cultural, linguistic, and political bonds with Ankara through the Organisation of Turkic States.

Azerbaijan’s application for full SCO membership further amplifies this Turkic dimension. The SCO thus offers Türkiye geopolitical leverage and a platform to weave together its identity as a NATO power and a Eurasian actor.

A summit with global consequences

From August 31 to September 1, Tianjin hosted a gathering that could redefine Eurasian geopolitics.

The SCO, once a narrow security forum designed to combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism, has now transformed into one of the most consequential regional alliances of the 21st century.

With China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran, Belarus, and the Central Asian republics as full members, the SCO now represents a vast bloc that accounts for more than 34 percent of global GDP.

This year’s summit was held against the backdrop of multiple global crises: the war in Ukraine, instability in the Middle East, Donald Trump’s renewed tariffs disrupting global trade, and the intensifying rivalry between Washington and Beijing.

In this turbulent context, the SCO stands out as one of the few venues where rivals such as China and India, or India and Pakistan, sit at the same table. Its ability to foster even limited cooperation has become a rare commodity in an era of deepening geopolitical fragmentation.

While all ten SCO heads of state and government attended the summit, the presence of India’s Narendra Modi was especially significant, marking his first visit to China since 2018 and signalling a potential thaw in Sino-Indian relations.

More than a dozen leaders from observer and dialogue partner countries and heads of major international organisations also participated in the two-day event.

Türkiye’s calculated balancing

Erdogan’s appearance as the guest of honour in this crowded arena underscores Türkiye’s growing importance to the SCO.

Ankara is not a full member, but its presence complicates easy narratives of East versus West. NATO and the SCO have long been viewed as representing opposing geopolitical poles.

Yet Türkiye, a founding NATO ally, is increasingly positioning itself as a connector rather than a captive of one camp.

This is not without risks. Ankara’s embrace of Eurasian forums has raised eyebrows in Western capitals, where scepticism toward China and Russia has hardened.

But Erdogan has proven adept at playing both sides—using Türkiye’s NATO membership to secure defence advantages, while leveraging Eurasian ties for energy, trade, and diplomatic clout.

The logic is pragmatic: in a multipolar world, hedging is survival.

Türkiye’s economy relies heavily on Western markets, but its energy needs are tied to Russia, while its long-term trade ambitions depend on China’s Belt and Road.

The SCO provides Ankara with a platform to balance these interests, while positioning itself as a mediator in global disputes—from the Ukraine war to Middle Eastern crises.

The SCO’s own test

The SCO itself faces divisions that limit its cohesion.

Long-standing rivalries between India and Pakistan, unease over China’s economic dominance, and disagreements on Russia’s war in Ukraine all complicate unity.

Still, even modest outcomes matter.

In the final Tianjin Declaration, the summit participants reaffirmed their commitment to security cooperation, including the fight against terrorism and drug trafficking.

The document also recorded new challenges: the leaders agreed to counter AI risks jointly and supported states' sovereign right to regulate the Internet.

Those gathered also condemned the US and Israeli strikes on Iran and the deaths of civilians in Gaza.

However, as in the Astana Declaration of 2024, the final document does not mention Ukraine.

For Türkiye, participating in these debates is itself an achievement. It allows Ankara to influence Eurasian agendas, deepen bilateral ties, and demonstrate to its Western allies that it has options beyond NATO and the EU.

Ankara’s recent moves—mediating between Russia and Ukraine on grain exports, seeking trade expansion with China while keeping open defence ties with NATO, and cultivating Central Asian partners—suggest it sees value in staying flexible.

That flexibility, however, is precisely what gives Türkiye leverage: it can listen to both Beijing and Moscow in ways Western Europe cannot, while maintaining influence in Brussels and Washington in ways the SCO states cannot.

In an age where a single pole no longer defines the global order, that dual identity makes Türkiye one of the few actors capable of navigating across divides.