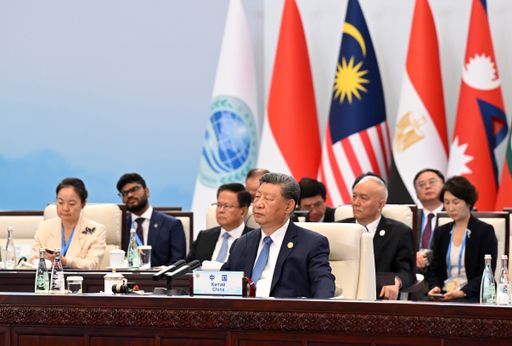

The most recent and largest-ever Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit brought together a record number of leaders in China, with over 20 countries and 10 international organisations in attendance.

While many see the SCO as a direct challenge to the US, this perspective misses the mark.

The organisation's future isn't shaped by Washington's policies. Instead, it depends on how well its members can navigate their own complex relationships.

For the SCO to become a truly influential global player, it must look inward and become a more unified, functional body.

The SCO's founding principle is the ‘Shanghai Spirit’, which emphasises mutual trust, benefit, equality, and respect for diverse civilisations.

In the wake of the Soviet Union's collapse, founding members united to secure borders, combat shared threats like terrorism, and forge a new model of international relations.

The SCO became a powerful platform for countries to assert their sovereignty, advocate for a multipolar world, and unite against what they saw as unilateral American hegemony.

The SCO's security achievements, particularly in counterterrorism, are widely regarded as a major success.

Its members were pioneers in creating a military trust framework for border regions, which has transformed thousands of miles of shared territory into zones of cooperation and friendship.

By boosting law enforcement and security cooperation and pushing back against foreign interference, the SCO has been effective in managing disputes and keeping the region peaceful and stable.

Economy, above all

The SCO's economic agenda may hold the most promise for its long-term viability.

While political debates capture the headlines, economic cooperation is the real force that can bind the organisation together.

The SCO is a crucial partner for China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), helping to launch massive infrastructure projects and expand trade across Eurasia.

As President Xi Jinping highlighted, annual trade between China and other SCO nations has soared past $500 billion, with China's total investment exceeding $84 billion.

The result is a vast network of connections, including nearly 14,000 kilometres of international roads and more than 110,000 China-Europe freight train journeys.

At the 25th Heads of State Council Summit in Tianjin, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan emphasised Türkiye’s dedication to strengthening ties with the SCO.

He lauded the organisation as a platform for "finding joint solutions to problems" and highlighted its "vital" role in boosting energy security and fostering strategic infrastructure partnerships.

This stance reflects Türkiye's commitment to diversifying its foreign policy and deepening its engagement in Eurasia, particularly with key players like China and Russia.

Since becoming a "dialogue partner" in 2012, Türkiye has repeatedly signalled its interest in strengthening ties with the SCO.

This engagement is a key part of Ankara's broader strategy to position itself as a multipolar power, balancing its long-standing Western alliances with new partnerships in the East.

By actively participating in SCO events and holding bilateral meetings with member states like China and Russia, Türkiye seeks to leverage its unique geographic and geopolitical position to promote its own and regional interests in trade, energy, and regional security.

This approach allows Ankara to pursue a more independent foreign policy and assert its influence in a changing global order.

Multiple challenges

Despite these accomplishments, the SCO faces significant internal challenges.

The organisation is a mix of nations with deep-seated rivalries and conflicting interests.

For example, ongoing border disputes and competition between India and China—two of its most powerful members—threaten to undermine its unity. Similarly, tensions between India and Pakistan have repeatedly hindered progress.

While the SCO's charter calls for peaceful dispute resolution, the organisation has consistently failed to act as an effective mediator among its members. The recent addition of new members like Iran and Belarus further complicates its internal dynamics.

For the SCO to achieve lasting success, it must evolve beyond being a merely symbolic club. It needs a more robust institutional framework to deliver concrete results.

The current system, which requires consensus for decision-making, allows any single member to block action, leading to perpetual inaction.

Without the authority to enforce its own resolutions or mediate conflicts, the SCO risks remaining a venue for discussion rather than a genuine force for change.

Beyond its regional focus, the Tianjin Summit marked a significant turning point for China’s international role.

President Xi formally introduced the Global Governance Initiative, a structured blueprint for a new global system outlining five core principles: upholding sovereign equality, respecting international law, practising multilateralism, adopting a people-centred approach, and focusing on action.

This initiative is a direct response to a world grappling with deficits in development, security, and governance.

Ultimately, the SCO's success isn't a matter of whether it can withstand pressure from the US.

The more critical question is whether it can overcome its own internal challenges.

The organisation must resolve its divisions, strengthen its institutions, and prioritise its economic mission.

This requires becoming a more results-driven and efficient body, including creating a development bank and speeding up the opening of a security threat response centre.

By transforming from a "talking shop" into a functional body with strong institutions and a clear agenda, the SCO can secure its place as a relevant and enduring force in the 21st century—a destiny entirely within its own control.