In a sweeping move aimed at restoring the United States' maritime strength, the Donald Trump administration has announced a series of aggressive policies targeting China’s dominance in the shipbuilding, logistics, and maritime sectors.

On Thursday, the US Trade Representative (USTR) unveiled a revised plan to impose port fees on Chinese-built vessels, modifying an earlier proposal in February that had suggested charges of up to $1.5 million per port call. Though scaled back, the new phased approach—starting October 14, 2025—still marks a significant shift, sending shockwaves across the global shipping industry. Fees will increase gradually over three years.

While the US administration claims that the policy is intended to curb China’s dominance in global shipbuilding, reinvigorate the ailing US shipyard sector, and bolster national economic security, critics and industry insiders say the move appears more symbolic than strategic.

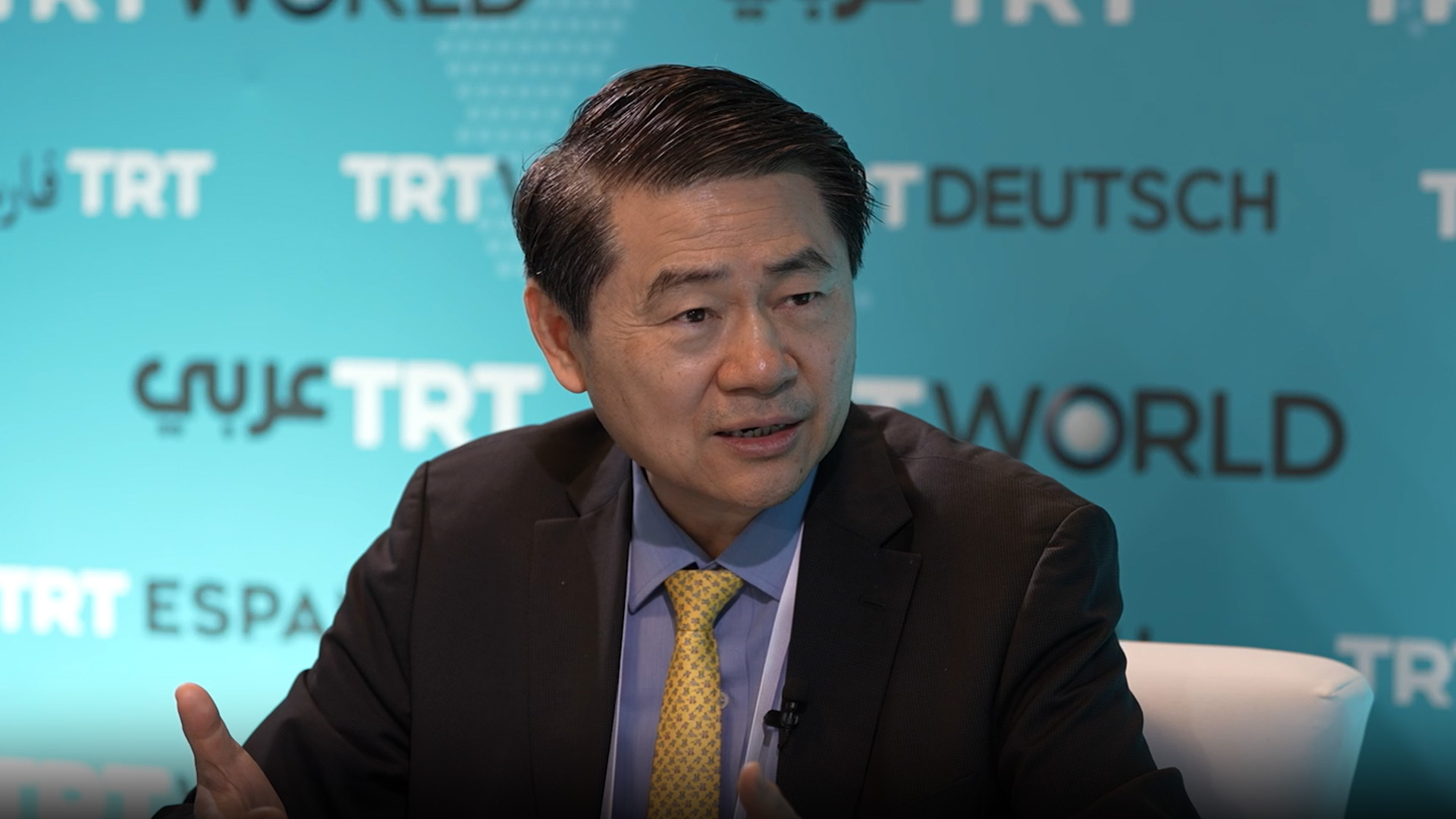

Tom Christopher Tong, founder and export director of Executive Exports based in Guangzhou, called the US plan “an outright silly concept,” describing it as “a political stunt aimed at stirring emotional appeal rather than solving structural industrial gaps.”

While acknowledging that a modest revival of America’s maritime sector might be feasible, Tong insists that reversing China’s dominance is a fantasy. “It’s a dream—completely unrealistic,” he told TRT World. “Why would such a reversal even be necessary in the first place?”

China on Friday condemned the United States over its newly imposed port fees, warning that the measures would ultimately harm American consumers and destabilise global trade.

Industry experts and trade associations also warn that the plan could backfire—raising consumer prices, disrupting freight logistics, and burdening American exporters with more expensive and complicated port calls.

Following intense industry backlash and warnings of higher costs cascading through global supply chains, the US significantly watered down its original proposal. Exemptions now apply to ships on US domestic routes, the Caribbean, US territories, and Great Lakes ports. US-based carriers such as Matson and Seaboard Marine, along with foreign ships arriving empty to load US exports, will also avoid the charges.

“Each exemption only highlights the weakness of a certain area and its dependence on Chinese-dominated shipping services,” Tong said, noting that the US is trying to send a signal of strength but has ended up “undermining itself by exposing its biggest weaknesses.”

An ambitious but improbable vision

The port fees are just one component of Trump’s broader Maritime Executive Order signed on April 9, 2025. The order outlines a multi-agency effort to rebuild America’s maritime industrial base and make US-built and -flagged vessels competitive again.

Measures include financial incentives, deregulation, workforce development, and the creation of maritime prosperity zones. The order also empowers the USTR to impose tariffs and service fees on Chinese-built ships and equipment such as container vessels and ship-to-shore cranes.

Yet many view the plan as an attempt to reclaim lost ground in an industry where the US has long lagged behind.

According to the latest data from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), China currently builds approximately 51 percent of the world’s commercial ships, with South Korea and Japan accounting for another 44 percent. The US, by comparison, builds less than 0.5 percent of the world's ships annually—about five commercial vessels per year.

Chinese shipyards produce over 1,700 vessels annually. In contrast, US shipyards cater primarily to military contracts, with little capacity or competitive edge in global commercial markets.

"Trying to catch up to China in commercial shipbuilding is like entering a Formula 1 race with a bicycle," said one maritime economist who declined to be named. "The capital investment, skilled labour, and technological ecosystem required is massive, and we are decades behind."

Tong underscored how futile the goal of reversing dominance really is. While he acknowledged a “short-term chilling effect” on China-US exports, he believed the long-term competitiveness of Chinese shipbuilders would remain unaffected. “These fees hinder cost effectiveness but do not inherently reduce the strength and value provided by Chinese shipbuilders.”

Potential supply chain disruption

About 80 percent of global trade moves via ocean freight. Imposing new fees and restrictions on this system, especially on the world's dominant fleet—which includes thousands of China-built vessels—risks creating bottlenecks and supply chain instability.

Furthermore, the global shipping industry is integrated and interdependent. Many US-based firms, like Seaboard Marine and Matson, rely on Chinese-built ships. While the USTR’s exemptions provide short-term relief, there remains widespread uncertainty over the long-term implications.

The American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA) warned that the cumulative effect of port fees and tariffs on cargo-handling equipment could reduce trade and raise prices for American consumers.

“We are deeply concerned that the newly announced port fees and shipping mandates are destined to have devastating consequences for American workers, consumers, and exporters,” AAFA said in an official statement.

Tong noted that Chinese firms are already adapting to the evolving US policy landscape. “China’s shipping industry is reducing US-bound booking volumes, raising sea freight rates, and revising trade contract terms to safeguard their interests,” he said, warning that these adjustments could undermine the viability of certain trade flows and potentially trigger a diversion of trade to countries like Vietnam.

Geopolitical storms

Some observers contend that the Maritime Executive Order is less about reviving US shipbuilding and more about increasing leverage over Beijing ahead of a potential new round of trade negotiations.

The phased implementation of fees, multiple carve-outs, and long-term targets stretching over decades suggest that immediate industrial revival is not the primary objective. Instead, analysts argue these measures are part of a broader geopolitical strategy aimed at containing China’s rise and extracting trade concessions.

Trump’s maritime strategy reflects a broader protectionist turn in US economic policy, reminiscent of the early 20th century when the Jones Act (1920), which aimed to shield US shipping from foreign competition. However, in an era defined by globalisation, digital trade, and transnational supply chains, such protectionist policies may yield diminishing returns.

“Might this be yet another policy that Trump intends to withdraw once the mere threat has served its desired purpose in pressuring his international counterpart?” asked Tong. “We will soon find out.”

As the international shipping community continues to respond and China mulls its countermeasures, one thing is clear: the seas may be calm now, but geopolitical storms are brewing.