Washington, DC — Spending nearly a year in space reshapes a person in ways no amount of training can truly prepare them for. The body unlearns gravity. Muscles shrink. Bones hollow. Vision falters.

A return to Earth is not just a descent through the atmosphere — it's a battle to reclaim one's own body.

US astronauts Barry "Butch" Wilmore and Sunita "Suni" Williams were meant to spend eight days aboard the International Space Station. Instead, a spacecraft failure left them marooned in orbit for 288 days.

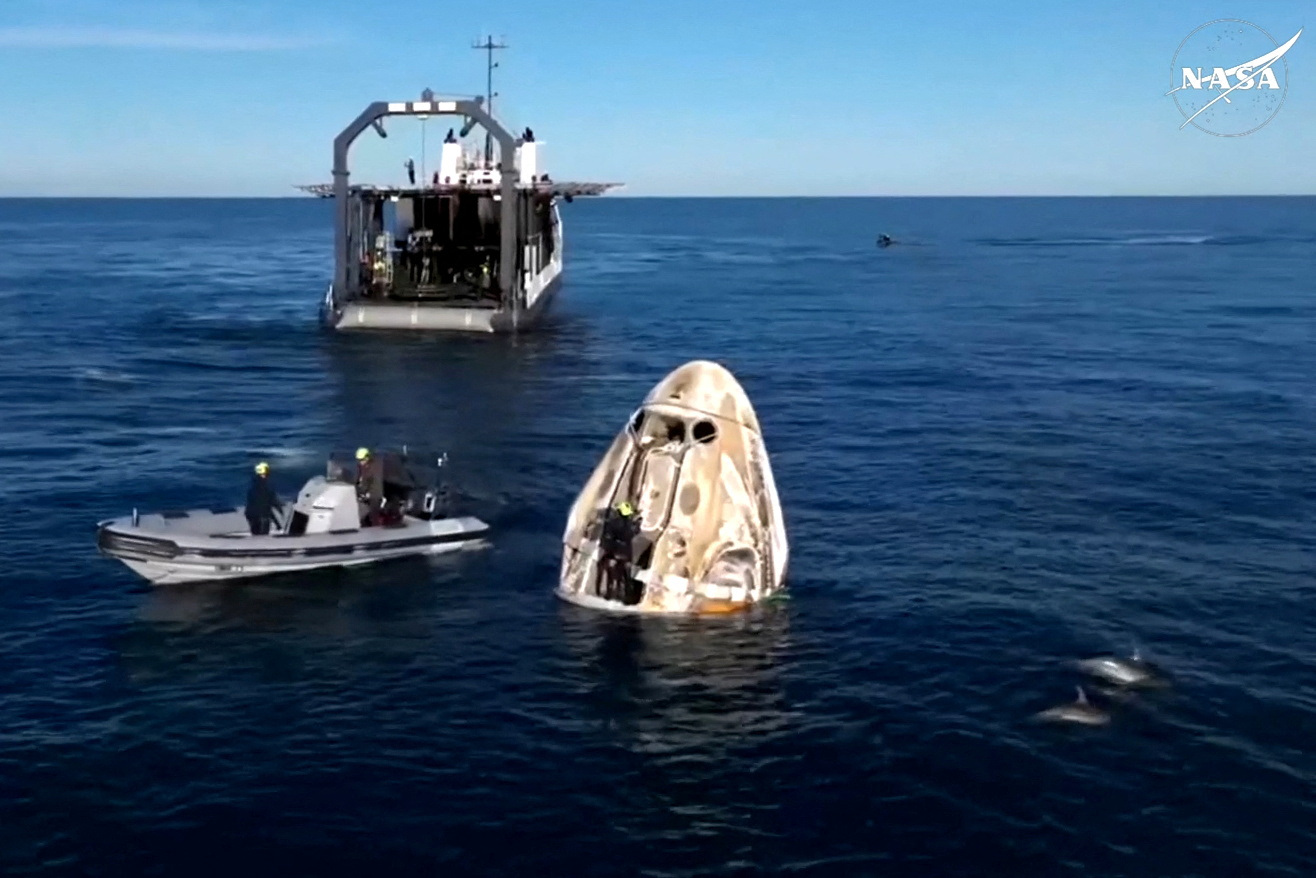

They drifted where Earth's pull could not reach them, their bodies slowly rewriting the laws of survival. When they finally splashed down off Florida's coast, they didn't just step onto solid ground, they staggered back into the weight of their own existence.

Cost of staying up there

Long-duration missions are no longer distant dreams. They are the next step. But the price is steep. The human body, sculpted by gravity, rebels against weightlessness.

Even with two hours of daily exercise — pulling against resistance bands, running on a harnessed treadmill — the body yields. Muscle shrinks. Bones surrender calcium, thinning at a rate that mimics a decade of ageing in mere months.

An astronaut's muscle and bone mass can diminish in space. Experts say the muscles that help maintain posture are affected the most because the muscles don't have to work as hard in space.

According to the Canadian Medical Association Journal, muscle mass can fall by nearly 20 percent in two weeks and by 30 percent in three-to-six-month missions.

Dr. Ariel Ekblaw, founder of the MIT Space Exploration Initiative, says the bodies of both Wilmore and Williams will have to retrain to Earth's gravity.

"When you're living in a long-duration microgravity mission, you do lose some of your muscle mass. Your heart weakens because it's not having to pump your blood against the force of gravity. And even funny things like your eyesight can change because the shape of your eyeball is a little different in microgravity," Ekblaw says.

A body betrayed

Floating is effortless. No strain, no weight. But that ease is a mirage. Without the need to hold itself up, the body slowly forgets how.

On Earth, even standing still engages muscles. In space, those same muscles slip into disuse. Studies show that bones fare worse. Each month in microgravity strips away 1 percent of bone density.

Over a year, that is more than a decade's worth of loss. Calcium leaches into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of kidney stones.

And then there's the head. Fluids drift upward, swelling the brain, pressing against the eyes. Some astronauts return with vision blurred, unable to focus the way they once did.

"It's really awful when you're on orbit and you come back and all of a sudden your leg weighs 30 pounds again. So you have to work on that. Strength is pretty good, but it'll take you a good months before you're up to full fighting form," former NASA astronaut Jack Fischer tells NPR.

Long road back

Gravity doesn't welcome them home — it crushes them. The first days are a blur of imbalance, nausea and bodies that no longer obey instinct. Walking feels foreign. Limbs are sluggish, bones fragile. Recovery is a slow and uncertain climb.

One of the stranger effects of microgravity is that astronauts actually grow taller in space, sometimes by as much as two inches. With gravity no longer compressing their spines, the discs between their vertebrae expand, stretching them out.

While this change is temporary and they often regain their actual height when back on Earth, according to NASA, epigenetics plays a role in the changes humans experience in space.

Changes in gene expression and shifts in the immune system are traces of spaceflight that don't fully fade.

Road to Mars

NASA and other space agencies are already charting a course to Mars, a journey spanning years, not months. The data from these prolonged missions is invaluable, but the question remains: Can the human body endure?

Can it survive the wear and tear of deep space without breaking beyond repair?

Every astronaut who returns offers another clue. Every step they take, shaky but determined, is another lesson in the limits of human endurance. The mission does not end when they land.

NASA doctors will be checking Wilmore and Williams for signs of cancer for the rest of their lives.

For them, the real test — the battle to reclaim themselves — has only just begun.